Tanzania's $10 billion port gamble

Can Bagamoyo become East Africa's shipping hub, or is it another Belt and Road project stuck in a rut?

Welcome back to the Off Site, brought to you by Aphex.

The Bagamoyo Port project promises to become East Africa's largest maritime hub, handling 20 million containers annually by 2045. That's 25 times larger than Tanzania's current main port, Dar es Salaam.

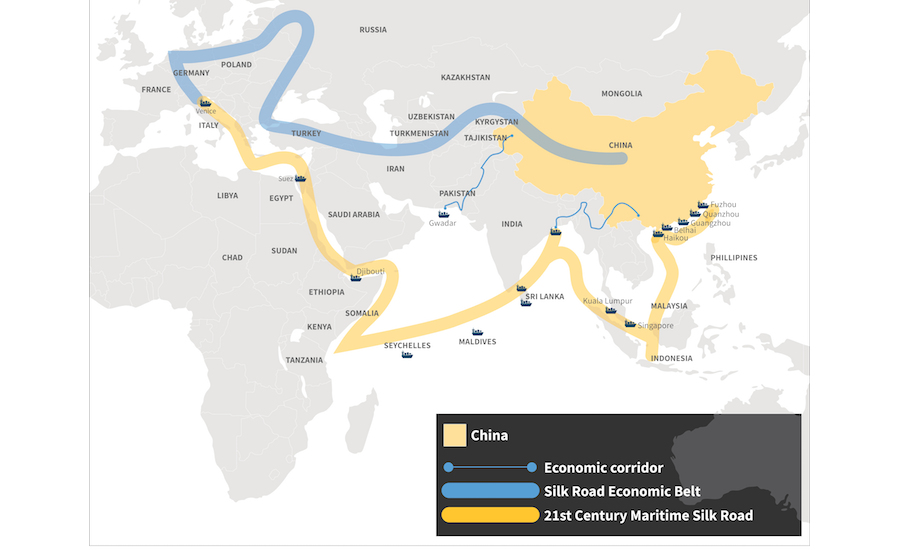

China has backed the scheme as part of its Belt and Road Initiative, envisioning Bagamoyo as a vital link to Africa’s interior, and to Indian Ocean shipping routes.

But after a decade of stops and starts, the project tells a familiar story of ambitious infrastructure promises meeting political and financial reality.

East Africa's port wars

Kenya and Tanzania have competed for decades to control East Africa's maritime trade. The Kenyan port of Mombasa and Tanzania's Dar es Salaam traditionally split the business, but both countries are now planning massive expansions.

Kenya is developing a new port at Lamu. Tanzania is pushing Bagamoyo. If completed as planned, both will be larger than any existing port in sub-Saharan Africa.

The competition makes sense. Dar es Salaam handles around 17 million tonnes annually but can't accommodate the largest container ships.

The port's congestion creates major delays — and these ripple through supply chains serving landlocked countries like Rwanda, Burundi, and the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.

Bagamoyo's proposed deep-water berths would handle 8,000+ TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent units) initially, with future expansion to accommodate 25,000-TEU ships – the largest container vessels in operation.

Construction puzzles

The engineering challenges start with location. Bagamoyo sits at the mouth of the Wami River delta, which creates ongoing sediment accumulation problems.

The project requires dredging 15 million cubic metres of sediment to achieve the 15.5-metre depth of the initial three berths. That sediment will keep returning, requiring continuous maintenance dredging, and racking up Bagamoyo’s operational costs.

Standard ports in calmer harbours face less aggressive waves and lower chloride exposure than open-ocean sites like Bagamoyo.

Because of this, engineers need to use marine-grade concrete with silica fume. These materials can be up to 30% more expensive than cheaper corrosion inhibitors or the epoxy-coated rebar suitable for harbour ports.

The port infrastructure will include a 2.8km curved breakwater using 7-tonne armoured concrete blocks to protect against the Indian Ocean’s massive waves.

Linking it up

A port is only as good as its connections inland. Bagamoyo needs entirely new transport links to function.

The railway component requires a 65km line connecting to Tanzania's existing TAZARA and Central Railway networks. This means building 12 bridges over mangrove estuaries, including a 480-metre span over the Ruvu River — the project's longest single structure.

The railway must also import 54,000 tonnes of UIC60 rails from China, highlighting the project's dependence on Chinese supply chains.

Road connections face their own problems. The planned 34km road to Mlandizi needs laterite soil stabilisation across 18km of swampy terrain — a complex and expensive foundation process.

Material logistics create additional headaches. Construction teams must deliver concrete daily from Dar es Salaam using a fleet of 40 mixer trucks. The 75km journey on the congested Bagamoyo-Dar highway creates bottlenecks that could slow the entire project.

The Special Economic Zone (SEZ)

Beyond the port, Bagamoyo includes plans for a 2,500-hectare Special Economic Zone to support 700+ industries and 15,000 workers.

Phase 1 involves clearing 887 hectares of coastal forest and grading 9,800 hectares total, displacing 180,000 cubic metres of earth. The zone also requires 200km of underground utilities for water, power, and fibre optics.

Industrial buildings will use prefabricated steel structures designed to withstand monsoon winds. Worker housing uses rapid-build modular units — a practical approach given the remote location and tight timeline.

Environmental mitigation adds complexity and cost. The project involves relocating 42 hectares of mangroves using hydraulic dredging techniques. Sediment curtains deployed during dredging aim to protect coral reefs near local fishing grounds.

A 50-megalitre per day desalination plant is planned to avoid straining local aquifers, whilst a circular drainage system with eight retention ponds will prevent seawater intrusion.

A troubled timeline

The project's history reflects the broader challenges facing Belt and Road investments in Africa.

The first framework agreement between Tanzania, China, and Oman was signed in 2013. Original partners included China Merchants Holdings and Oman's sovereign wealth fund in a joint venture structure. In 2015, former president Jakaya Kikwete promised the port would be completed within three years.

However, by 2019, then-President John Magufuli suspended the project, accusing China of imposing "exploitative terms," including excessive tax exemptions and compensation for operating losses. China Merchants Holdings and Oman's SGRF exited due to disputes over revised terms.

Current President Samia Suluhu Hassan relaunched negotiations with China Merchants Holdings in 2021, describing them as "a national priority." As AEDIC Consultants explain, the port isn’t just about infrastructure — it’s both “a symbol of China's growing influence in Africa and Tanzania's vision of becoming a global logistics hub.”

In 2024, the government completed compensation for landowners displaced by the SEZ — a necessary step that had delayed progress for years. Work officially began in 2025 with an initial budget allocation of TZS 22 billion (approximately $9.3 million) for Phase 1 berth foundations and access roads.

The current status of the project

As of February 2025, Tanzania has signed memoranda of understanding with companies from China, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia. But these cover only preliminary activities, not actual port construction.

Plasduce Mbossa, the Tanzania Ports Authority Director General, emphasised the modest scope, clarifying that MoUs entered with those firms cover preliminary activities, not the construction of the port.

The project faces practical constraints that affect most major African infrastructure developments. Tanzania's 2021 Local Content Regulations require 45% of materials to be sourced domestically by 2026. Monsoon delays are built into planning, with 14-week annual work stoppages anticipated during heavy rains.

On the pod

This week, the team covers: the merger between Australian platform E1 and UK-based C-Link; the record-breaking $3-4 billion flowing into construction tech startups in early 2025; and Acciona topping the UK contractor league table for the first time with a £400 million waterworks win.