North China is ‘borrowing’ 44.8 billion cubic metres of water from the South

Three routes will divert water from the Yangtze River Basin to China’s parched north

At Aphex, we've covered some massive projects, from vast offshore windfarms to from-scratch capital cities. But China’s South-North Water Transfer Project (pinyin: Nánshuǐ Běidiào Gōngchéng; literally the ‘project of diverting water in the south to the north’) is the type of vast project that boggles the mind. It’s bigger in scale, cost, and complexity than the Three Gorges Dam.

The three paths of the South-North Water Project will move 44.8 billion cubic metres of water each year, from China’s relatively wet South to its more arid and heavily populated North. The project is the equivalent of re-channeling the Mississippi River to provide water to Boston, New York, and Washington.

In the words of journalist Aaron Jaffe, it’s an effort to “replumb the nation” — and, in doing so, physically reconfigure China’s vast and ancient hydrogeography

“Borrowing some water would be good”

The idea traces its legacy back to Mao Zedong, who in 1952 reportedly said that, “There’s plenty of water in the south, not much water in the north. If at all possible, borrowing some water would be good.”

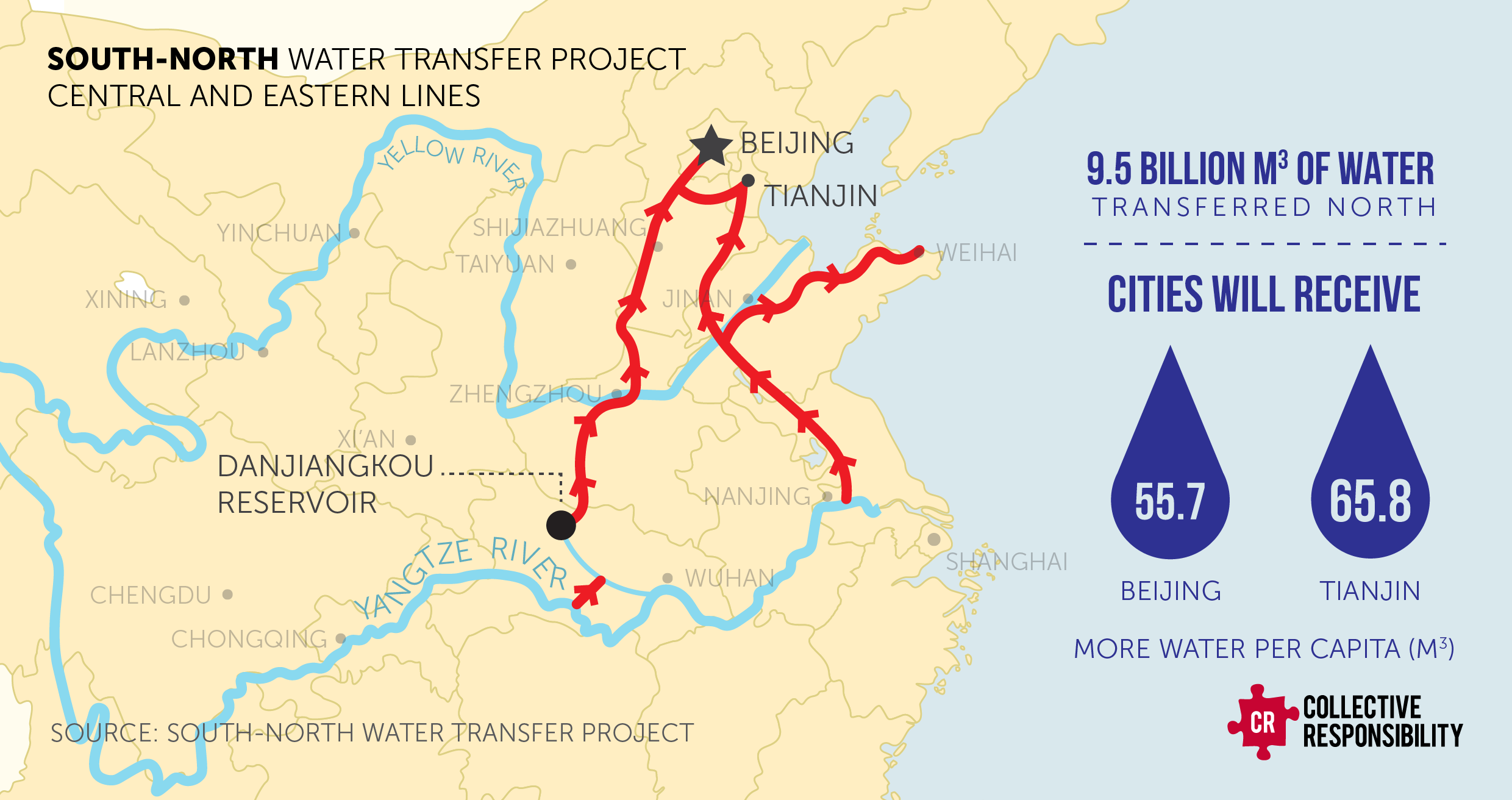

By 2003, work had started on the first of three proposed routes, each using different methods to divert water from the south’s rivers, tributaries, and reservoirs. They connect four major river basins (the Yangtze, Huaihe, Yellow, and Haihe), making the project the world’s largest interbasin transfer.

The Eastern route was built alongside the existing, defunct Grand Canal. Construction began in 2003, and its first phase was completed in 2013. It provided water first for cities in Shandong province and, later, 12 million residents of Tianjin city.

The central route, completed in 2014, begins in the Danjiankou Reservoir in Central China. The route is over 1,100 kilometres long and runs through Henan and Hubei regions before reaching Beijing and Tianjin, flowing beneath railways at 44 places and making more than 700 river crossings on the way.

The Western Route will divert from three of the Yangtze River’s tributaries (the Tongtian, Yalong, and Dadu Rivers) into the Yellow River, across the Tibet Plateau to north-west China. This route remains in its proposal stage, although work will reportedly be finished in 2050.

Amid all this are dozens of (relatively) smaller projects, from bridges over new canals, plumbing and legislative work, smaller local diversions, pumping stations, and water purification plants.

Yellow River crossing

To flow from the Danjiankou Reservoir to Beijing, engineers had to figure out how to cross the Yellow River — one of China’s central rivers, which cuts across the country from roughly west to east. It was a vital challenge to overcome, and one of the project’s most impressive feats of engineering.

Two tunnels, each 4.7 kilometres long, were buried 40 metres below the riverbed. The tunnels were partly constructed in segments, partly cast in situ, and separated by cushioning material that helps seismic resilience.

Both are 7 metres in diameter and can withstand water pressure of up to 0.51 MPa in shifting, water-saturated sandy soils. They’re also double-cased—one layer 0.4 metres thick, the other 0.45—helping the tunnels withstand pressure from within and without.

Getting the tunnels built involved using a slurry balanced shield machine in a Chinese tunnel-boring project. Stones and ancient tree trunks littered the river bed, requiring careful navigation and constant adjustment of the TBM’s parameters. And, because the soils were soft and waterlogged, the shield machine supported the excavated space until the tunnel segments could be installed.

In 2020, when the route had been operational for five years, the tunnels had already facilitated the flow of 30 billion cubic metres of water. In 2024, according to Chinese state news, “nearly 80 percent of the water consumed in Beijing's urban areas [had] made this 15-day journey from Danjiangkou.”

.webp)

Danjiankou Dam heightening

The Yellow River Crossing might be the most dramatic engineering feat in the multi-decade project, but it’s not the only impressive one.

Because the Central Route needed water to flow downhill to Beijing, the Danjiangkou Dam wall had to be heightened to increase the reservoir’s capacity. Originally 162 metres high, an additional 14.6 metres of wall added 11.6 billion cubic metres of storage capacity to the Reservoir. The new-to-old integration involved using advanced concrete bonding techniques, which all had to be done while maintaining dam operations.

The Eastern route, which traces the path of the Grand Canal, required massive prestressed concrete aqueducts that could support 420 m³/s flow rates. These aqueducts traverse 387km of soils that swell and shrink with moisture changes, threatening slope stability. Specialised treatments and real-world testing were conducted to ensure they were viable long-term.

Who's building it?

A project of this scale is a behemoth on every scale — logistical, political, and economic, covering planning, approvals, procurement, and construction.

The State Council officially approved the project in August 2002, with a groundbreaking ceremony in December 2002.

The project’s developer is a special limited-liability company (South-to-North Water Transfer Project Company) established by the central government. GCW Consulting managed infrastructure development plans, and project management is split between the State Development and Planning Commission, the Ministry of Water Resources, the Ministry of Construction, the State Environment Protection Administration, and China International Engineering Consultant Corporation.

Provincial water supply companies manage local sections, while major Chinese state-owned enterprises, including Sinohydro, China Gezhouba Group, and China State Construction Engineering Corporation, have been involved in construction and engineering.

What does it cost?

The original estimate was 124B CNY—around $15B USD. In straight numbers, the last reported cost of the whole project was USD $62 billion. But the project is so huge and multifaceted that it’s hard to track the total cost, let alone where the money to pay for it is coming from.

The question of cost is not merely economic. As Edward Chong reported in 2011, “The central question for people in Hubei is whether the Han River, crucial to farming and industrial production hubs, will be killed to keep north China alive.”

The building of canals and tunnels and the expansion of dams have also led to mass resettlements. According to China’s State Council Information Office, “345,000 people were resettled due to the elevation project of the Danjiangkou Dam in the project's central route” between 2010 and 2011.

Southern regions like Sichuan have expressed serious concerns about the north’s water consumption, which drains their local resources but might outstrip the south’s capacity to meet demand. In 2011, Circle of Blue reported that Sichuan had filed “formal oppositions to building the third and final transfer line in the west.”

Rivers reimagined

As of 2024, the central and eastern routes had delivered a reported 76.5 billion cubic meters of water from the verdant south to the arid north.

As water advocates Circle of Blue point out, the vast water transfer was initially seen as the most practical and credible option to slake the north’s thirst. In the last decade, though, “technologies like desalination have decreased in cost, while inputs to building canals, like labor, have increased.”

For some, the transfer is a baffling solution: why not, for example, focus on managing population distribution in line with water availability instead? For others, it’s a triumph of engineering — both in line with China’s innovative past, and future-proofing its continuing expansion.

Either way, the message is clear: even geography can be brought in line with China’s will. China has clearly decided that proving this point is worth the cost.